In the Mycelium Matrix: Mushroom Hunter’s Insights

Mushrooms 101, insights, a weekend journey into nature's hidden networks...

#4 Your Daily-ish Knowledge Dose

P.S. If this post sparked your curiosity, hit the ❤️ button—it helps more curious minds discover this journey!

Wonderful weekends, like breathing in the forest...

A gentle squeeze, and spores drift like whispers of forgotten tales, carrying away the week's weight.

Last weekend, I went mushroom hunting, which inspired me to write this blog. I've been fascinated by mushrooms for as long as I can remember. One of my favorite core memories from childhood is going into the forest with my grandmother to find mushrooms. Anyone who’s done this even once knows the thrill of searching and finding them…

Stepping into a forest to hunt for mushrooms feels like trespassing into an ancient world — a hidden network where the lines between species blur and identities overlap.

My mushroom hunt recently led me to the heart of this entangled world, where nature's complex tapestry unfolds in myriad ways. Following mushroom tracks here feels like stepping off the map of familiar biological structures and into what Darwin once called an "entangled bank" — a place where beings are so woven together that definitions falter.

The fungi I found were like mystical guides, leading me deeper into the rich, interspecies dialogues occurring underground.

The Fungal Underground

Mushrooms are merely the fruiting bodies, the visible tips of an underground web formed by the thread-like hyphae of fungi. These hyphae spread through the soil like living veins, their networks touching, supporting, and even feeding neighboring species in what some have aptly named the “woodwide web.”

Imagine if we could make the soil transparent and walk into this labyrinthine structure — we’d find ourselves encased in a shimmering, ethereal matrix of fungal filaments, branching like neurons across the earth.

Fungi are not like plants; they don’t photosynthesize but instead consume nutrients, breaking down dead organic matter. Their way of consuming is generous, almost alchemical.

They exude digestive enzymes that break down their environment externally, drawing nutrients inward but also releasing vital minerals that plants, animals, and other fungi rely on. Fungi are thus the unsung alchemists, the hidden architects of ecosystems, creating soil from rock, breaking down deadwood, and forging spaces for life.

Mycorrhizal Mysteries

Some fungi, like ectomycorrhizal fungi, form intimate partnerships with plants, interweaving with roots to exchange nutrients. In these mutualistic relationships, both parties are transformed — the fungus is nourished by the plant's sugars, and in return, it helps the plant absorb minerals and water.

These fungal-root alliances can stretch across entire forests, forming networks that connect trees, even enabling them to share resources and communicate threats. Imagine a beech tree warning a distant oak of an impending drought or pest through fungal whispers in the soil.

This dynamic isn’t always harmonious; at times, the fungus might shift to parasitism, taking more than it gives. Yet the overall balance of this network sustains life on an immense scale. Mycorrhizal networks enable forests to function almost as a single organism, resilient and responsive to change.

It’s as if life here isn’t built on the survival of the fittest but the survival of the connected.

My mushroom hunt brought me face-to-face with this underground network’s dazzling fruit. I found mushrooms of many forms and hues, each telling a story of its unique role in the ecosystem.

Inspired by this universe, I’m starting a long-term collection to create a kind of “periodic table” of mushrooms. This is just the beginning—what do you think so far? For those interested in learning more, I’ve included some easy-to-digest information below to dive deeper into the world of mushrooms. Enjoy learning!

A Closer Look: Insights from My Mushroom Hunt Adventure

1. Beefsteak Fungus (Fistulina hepatica) – FH

Looks Like Meat: This mushroom resembles raw steak and even “bleeds” red juice when cut.

Tangy and Edible: With a slight sourness, it’s edible and has a surprisingly meaty texture, popular for plant-based dishes.

Wood Artistry: It creates beautiful dark streaks in oak wood, prized by artisans for its marbled look.

Antioxidant Power: Known for immune-boosting properties, it’s rich in antioxidants and valued in traditional medicine.

Tree Health Signal: Often found on weakened trees, it aids in decomposition, returning nutrients to the soil.

2. Whitelaced Shank (Megacollybia platyphylla) – MP

Cluster Grower: Often found in large, ground-covering clusters, giving it a unique presence on the forest floor.

Mildly Edible: Although edible, it’s not highly sought after due to its bland taste, mainly gathered by curious foragers.

Forest Recycler: Plays an essential role as a decomposer, breaking down leaf litter and dead wood, helping enrich the soil.

Adaptable Survivor: Known for its resilience, it thrives in diverse environments, from dense woodlands to challenging soils.

3. Shrimp Russula (Russula xerampelina) – RX

Seafood Aroma: Known for its faint shrimp-like smell, which helps foragers identify it among other Russulas.

Edible with a Nutty Flavor: Enjoyed for its mild, nutty taste, it’s a favorite for wild mushroom enthusiasts.

Metal Tolerance: This mushroom can absorb heavy metals, making it useful for studying soil contamination.

Forest Partner: Forms symbiotic relationships with trees, supporting nutrient exchange and forest health.

4. Porcelain Fungus (Oudemansiella mucida) – OM

Glass-Like Beauty: Known for its translucent, glossy cap that resembles porcelain, adding a delicate glow to damp woodlands.

Slimy but Edible: While technically edible, its slimy texture deters most people from cooking with it.

Antimicrobial Potential: Contains compounds being studied for natural antibiotic properties, sparking scientific interest.

Wood Decomposer: Often found on dead beech trees, it plays a key role in breaking down wood and recycling nutrients in the forest ecosystem.

5. (Panus velutinus) – PV

Velvety Texture: Recognizable by its soft, velvety surface, which sets it apart from other forest mushrooms.

Mildly Edible: Edible but with a bland taste, it’s not popular in cooking, though it occasionally adds texture to soups and stews.

Resilient Decomposer: Thrives in various environments and helps break down organic material, aiding soil health.

Potential for Pollution Cleanup: Shows promise in bioremediation research due to its ability to survive in and possibly detoxify contaminated soils.

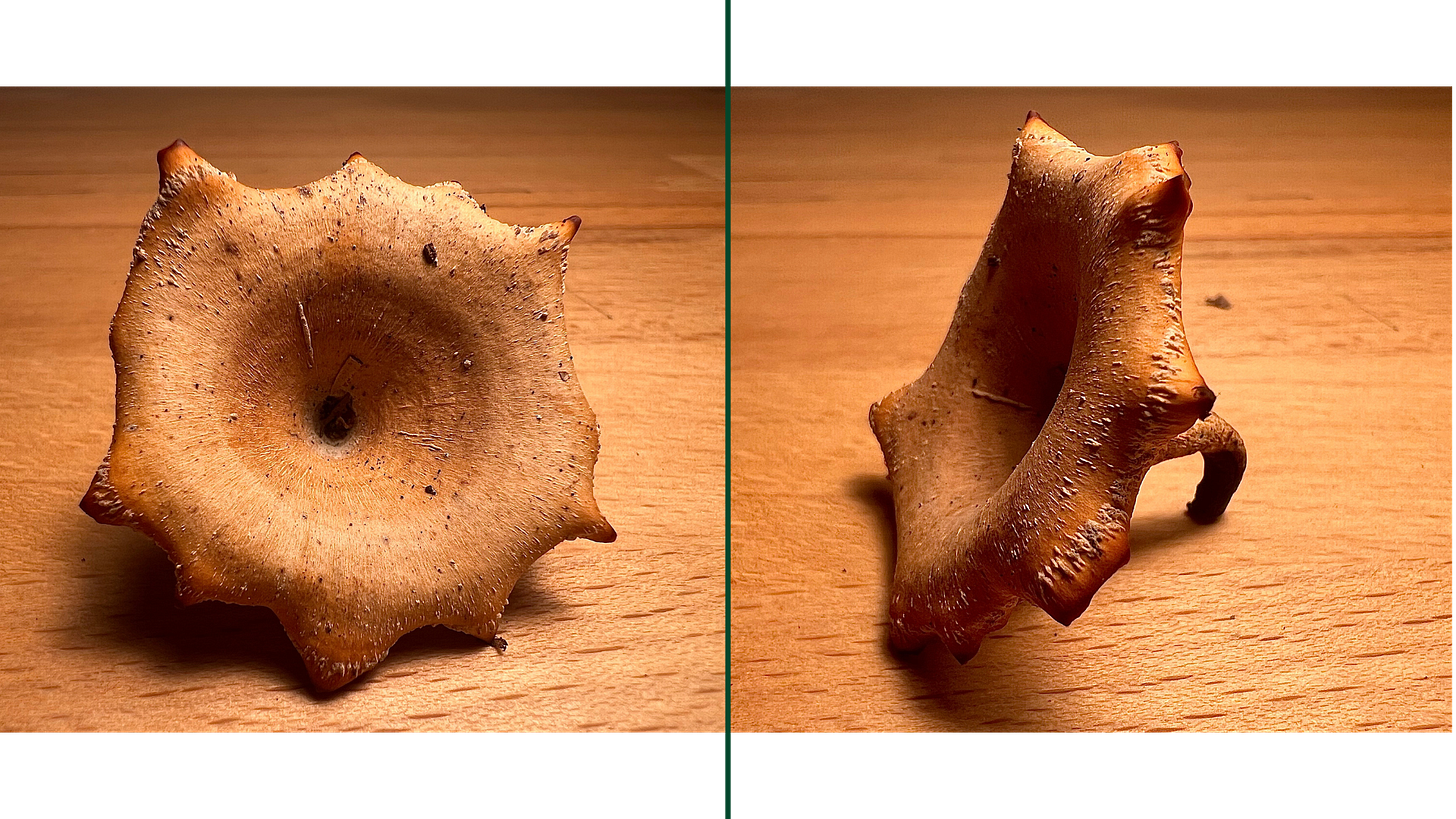

6. Common Puffball (Lycoperdon perlatum) – LP

Puff of Spores: Famous for releasing a “smoke” of spores when pressed, making it a fun find in the forest.

Edible When Young: Safe to eat before the spores mature, with a mild, earthy flavor enjoyed by foragers.

Medicinal History: Traditionally used for its coagulant properties to help stop bleeding in small wounds.

Natural Recycler: Grows on decaying matter, playing a crucial role in nutrient recycling within forest ecosystems.

7. Parasol Mushroom (Macrolepiota procera) – MP

Towering Presence: Easily recognized by its tall stem and large, umbrella-like cap, making it a striking sight in the woods.

Deliciously Edible: Prized for its nutty, savory flavor, it’s a favorite among foragers and often prepared like a meat substitute.

Easy to Identify: Its unique shape and patterns help avoid confusion with toxic look-alikes, making it a safer choice for beginners.

Forest Floor Resident: Often found in open woodlands and grassy clearings, it contributes to forest diversity and soil health.

8. Honey Mushrooms (Armillaria mellea) – AM

Bioluminescent Mycelium: The mycelium of Honey Mushrooms can glow faintly in the dark, a phenomenon known as “foxfire,” which adds a magical touch to its underground presence.

Edible but Requires Caution: While edible, Honey Mushrooms must be cooked thoroughly, as they can cause mild digestive upset if undercooked.

Forest Giant: A close relative, Armillaria ostoyae, holds the title as the world’s largest known organism, covering an estimated 3.5 square miles (9.1 km²) in Oregon. This “humongous fungus” is estimated to weigh around 35,000 tons!

Tree Parasite: Honey Mushrooms are known to parasitize trees, often leading to root rot, which can weaken or kill their hosts. Despite this, they play a role in forest ecosystems by helping recycle nutrients from dead trees.

9. (Russula lutea) – RL

Sunny Yellow Cap: Known for its bright yellow color, which makes it easy to spot in the forest and helps distinguish it from toxic red-capped Russulas.

Mildly Edible: While edible, it has a bland, slightly nutty flavor, making it less popular than other wild mushrooms for cooking.

Forest Symbiosis: Forms beneficial relationships with tree roots, helping trees absorb nutrients more efficiently and contributing to a healthy ecosystem.

Indicator of Forest Health: Its presence often signals a balanced, thriving woodland, as it’s typically found in symbiotic partnership with healthy trees.

10. Deer Mushroom (Pluteus cervinus) – PC

Delicate, Earthy Flavor: Edible with a mild, earthy taste, though not widely sought after, it can be a nice addition to soups and stews.

Woodland Decomposer: Grows mainly on decaying wood, breaking down lignin and helping recycle nutrients back into the forest soil.

Adaptable and Resilient: Thrives in various habitats, from deep forests to urban parks, making it a common find for mushroom hunters.

Unique Genetic Lineage: Its DNA reveals it belongs to a distinct group of fungi, making it an interesting subject for studies on fungal evolution.

11. Sooty Head (Tricholoma portentosum) – TP

Charcoal-Hued Cap: Often called “Charbonnier” in French, meaning “coalman,” due to its distinctive sooty-gray cap, which blends well into forest floors, especially in coniferous areas.

Edible with Precautions: While it has a pleasant, nutty flavor, it should always be cooked thoroughly, as raw or undercooked specimens can cause mild digestive discomfort in some individuals.

Cold Weather Friend: This mushroom thrives in cold weather, often appearing late in the season, making it a prized find for winter mushroom hunters.

Soil Health Indicator: Its growth in undisturbed forests signals healthy, nutrient-rich soil, adding ecological value as a marker of forest quality.

12. The Sickener (Russula emetica) – RE

Bright Red Warning: With its striking red cap, this mushroom is hard to miss—but its color also serves as a natural warning.

Toxic and Inedible: True to its name, it causes nausea and vomiting if consumed, making it best admired rather than eaten.

Forest Helper: Despite being toxic to humans, it plays a beneficial role in the forest, forming symbiotic relationships with tree roots and helping trees absorb nutrients.

Animal Deterrent: Its toxicity is thought to deter animals from eating it, allowing it to thrive undisturbed in the forest ecosystem.

13. Red Cage (Clathrus ruber) – CR

Alien Appearance: Known for its vibrant red, cage-like structure, this mushroom looks otherworldly and stands out on the forest floor.

Foul Odor: Emits a strong, unpleasant smell to attract flies, which help disperse its spores—a unique reproductive strategy among fungi.

Inedible and Untouchable: While not highly toxic, its odor and unappetizing structure make it unsuitable for consumption.

Natural Decomposer: Grows on decaying wood and organic matter, contributing to nutrient recycling and enriching forest soil.

14. Sulphur Tuft (Hypholoma fasciculare) – HS

Poisonous with a Bitter Taste: Highly toxic and extremely bitter, Sulphur Tuft can cause severe digestive issues if ingested, so it’s strictly off the menu.

Bioluminescent Glow: The mycelium of Sulphur Tuft has a fascinating secret—it’s bioluminescent and can emit a faint greenish glow in the dark! This eerie illumination is a rare trait among fungi.

Woodland Decomposer: It thrives on decaying logs, playing an important role in breaking down dead wood and returning vital nutrients to the ecosystem.

Dense Clusters: Often found in large, eye-catching clusters, Sulphur Tuft creates striking displays on fallen trees but is best admired from a distance due to its toxicity.

15. Death Cap (Amanita phalloides) – AP

Innocent Appearance, Deadly Effect: Despite its pale, innocuous look, the Death Cap is one of the deadliest mushrooms, responsible for the majority of mushroom-related fatalities worldwide.

Potent Toxins: Contains amatoxins, which inhibit RNA synthesis, leading to liver and kidney failure. Just half a cap can be fatal, making it incredibly dangerous even in small amounts.

Delayed Symptoms: Symptoms often don’t appear until 6-12 hours after ingestion, giving a false sense of safety. This delay makes treatment challenging, as damage to organs is already underway.

Historical Poisonings: Believed to be the cause of Emperor Claudius’ death in ancient Rome and implicated in other historical poisonings, earning it a notorious reputation.

16. A Mediterranean Delicacy (Amanita codinae) - AC

Distinctive Brown-Warted Cap: With a whitish to pale brownish cap (ranging from 50-90 mm wide, occasionally reaching up to 130 mm), A. codinae is easily recognized by its striking brown warts or scales, which are concentrated around the center. This unusual texture sets it apart from many other Amanita species.

Uncertain Edibility: While its exact toxicity remains unknown, it’s safest to avoid A. codinae, given the notorious toxicity of many Amanitas. The mushroom begins with a faintly pleasant odor that can turn slightly off-putting as it ages, and it has a mild taste—not that it should be sampled!

Southern Distribution: Known for its primarily southern range, A. codinae’s recent discovery in Turkey marks a significant expansion of its known distribution, offering valuable insights into fungal biogeography for mycologists.

Unique Ecological Niche: Unlike most Amanitas, A. codinae does not associate with woody plant roots. Instead, it’s commonly found in open pine woodlands on calcareous soils, indicating it fills a unique role in its environment.

17. Zoned Rosette (Podoscypha multizonata) - PM

Floral Appearance: This mushroom forms rosette-like, layered clusters that resemble a blooming flower, giving it a delicate, ornamental look on the forest floor.

Rare and Uncommon: Zoned Rosette is relatively rare, found mainly in older woodlands, especially around decaying hardwood stumps, making sightings a special treat for mushroom enthusiasts.

Inedible Beauty: Although visually captivating, it’s not edible due to its tough, leathery texture and lack of culinary value.

Soil Stabilizer: Its sprawling growth helps stabilize soil around decaying wood, subtly supporting the forest ecosystem and preventing soil erosion.

Intricate Zoning Pattern: The mushroom's “zoned” appearance comes from its concentric rings, which alternate in color and give it a distinctive, textured look that adds to its visual charm in nature.

18. Tinder Fungus or Hoof Fungus (Fomes fomentarius) – FF

Ancient Fire Starter: Known for centuries as a natural tinder, this fungus was used by early humans, including Ötzi the Iceman, to start fires due to its ability to catch and hold a spark.

Hoof-Like Shape: Its tough, hoof-like form grows on the sides of trees, especially birches and beeches, making it easily recognizable in the forest.

Medicinal Uses: Traditionally used in folk medicine for its antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and immune-boosting properties, it’s now being studied for potential applications in modern medicine.

Sustainable Leather Alternative: Researchers are exploring its fibrous interior as a sustainable material for eco-friendly leather substitutes, thanks to its durability and texture.

Tree Decomposer: Although it often grows on living trees, it primarily helps break down dead wood, recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem and supporting forest health.

19. Artist’s Conk (Ganoderma applanatum) – GA

Nature’s Canvas: When scratched, the white surface of this fungus reveals a brown underlayer, allowing artists to etch detailed images—hence the name "Artist's Conk."

Medicinal Properties: Used in traditional medicine for its anti-inflammatory, immune-boosting, and antioxidant properties, similar to its cousin, Reishi. It’s often made into tinctures and extracts.

Long-Lived and Persistent: This perennial mushroom can grow for years, adding new layers annually, which gives it a unique, layered appearance and allows it to reach considerable size.

Natural Decomposer: Grows mainly on dead or dying trees, helping break down tough lignin and cellulose and returning vital nutrients to the forest ecosystem.

Carbon Capture Potential: Recent studies suggest it may play a role in sequestering carbon, making it a quiet but valuable ally in forest ecosystems.

20. Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) - LE

Culinary Staple: Renowned for its rich, savory flavor, Shiitake is a beloved mushroom in Asian cuisine and is used in a variety of dishes, from soups to stir-fries.

Medicinal Powerhouse: Known for its immune-boosting properties, Shiitake contains compounds like lentinan, which have been studied for potential anti-cancer, cholesterol-lowering, and antiviral effects.

Natural Vitamin D Source: When exposed to sunlight, Shiitake mushrooms produce high levels of vitamin D, making them a valuable source of this nutrient for plant-based diets.

Sustainably Cultivated: Often grown on hardwood logs or sawdust, Shiitake is one of the most sustainably farmed mushrooms, with a lower environmental impact compared to many other food sources.

Skincare Ingredient: Shiitake extracts are also used in skincare for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits, believed to help with skin aging and hydration.

21. Reishi or Lingzhi (Ganoderma lucidum) – GL

“Mushroom of Immortality”: Revered in traditional Chinese and Japanese medicine for centuries, Reishi is famed for its longevity-promoting effects, earning it the title “Mushroom of Immortality.”

Immune Booster: Packed with polysaccharides and triterpenes, Reishi is believed to enhance immune function, reduce inflammation, and help the body adapt to stress, making it a popular adaptogen.

Stress Reliever: Known to support mental calm and reduce anxiety, Reishi is commonly used as a natural supplement for stress relief and improved sleep quality.

Anti-Cancer Potential: Reishi is actively studied for its potential in cancer therapy, particularly its compounds that may inhibit tumor growth and support chemotherapy effectiveness.

Versatile Use: While tough and bitter when raw, Reishi is typically consumed as a tea, tincture, or powdered extract, making it easy to integrate into daily wellness routines.

22. Lion's Mane (Hericium erinaceus) – HE

Brain-Boosting Mushroom: Known for its potential cognitive benefits, Lion’s Mane contains compounds that may stimulate nerve growth factor (NGF), which is essential for brain health and memory support.

Unique Appearance: Its cascading, tooth-like spines give it a fluffy, mane-like look, making it one of the most visually distinctive mushrooms found in forests.

Nootropic Properties: Often used as a natural nootropic, Lion’s Mane is popular in wellness circles for potentially enhancing focus, mental clarity, and mood.

Immune and Gut Health Support: Contains beta-glucans and antioxidants that may strengthen the immune system and support gut health, adding to its appeal as a functional food.

Culinary Delight: With a mild, seafood-like flavor and meaty texture, it’s often used as a vegan substitute for crab or lobster, lending a unique taste to stir-fries and soups.

23. Beautiful Bonnet (Mycena renati) – MR

Bioluminescent Glow: This tiny mushroom emits a gentle greenish glow in the dark, creating a magical effect on the forest floor and adding to its allure.

Tree Decomposer: Commonly found on decaying wood, Mycena renati helps break down fallen branches and logs, recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem.

Inedible but Fascinating: Although it’s not edible, its unique bioluminescent properties make it a favorite among mushroom enthusiasts and night-time nature explorers.

Indicator of Forest Health: Its presence often signals a well-balanced ecosystem, as it typically thrives in undisturbed, healthy forests rich in decaying wood.

Closing Thoughts

In the woods, following mushroom tracks, we encounter a silent, persistent force shaping the world in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Perhaps by embracing fungi’s lessons of entanglement and resilience, we too can learn to live as part of the greater web of life, nourishing each other and our shared planet in ways that go beyond individual gain. This mycelial wisdom may hold the key to rethinking our role in the world — not as conquerors of nature but as participants in a vast, interconnected dance.

Thanks :)

P.S. If this post sparked your curiosity, hit the ❤️ button—it helps more curious minds discover this journey!

And if these ideas got you thinking, consider sharing or recommending the journey to others.

Wanna read more?

Stay tuned for the next blog post coming!

Until then, take care!

You know way more than I, but living in Vancouver, mushrooms 🍄 are a plenty and have recently taken an interest!